Higher pricing would undoubtedly expand the total economic picture. It may even provide some incentives to transform the uneven distribution of membership payments into an overall pot that benefits the top artists regardless of what particular subscribers choose to play.

However, the reduction of Spotify's stock price last year suggests that this strategy is laden with danger. Nobody knows what price increases will do to demand in a shaky economy. We're approaching saturation, with platforms only gaining subscribers by stealing from others. Spotify is competing with large internet companies who see music as a loss leader, packaged in with other services.

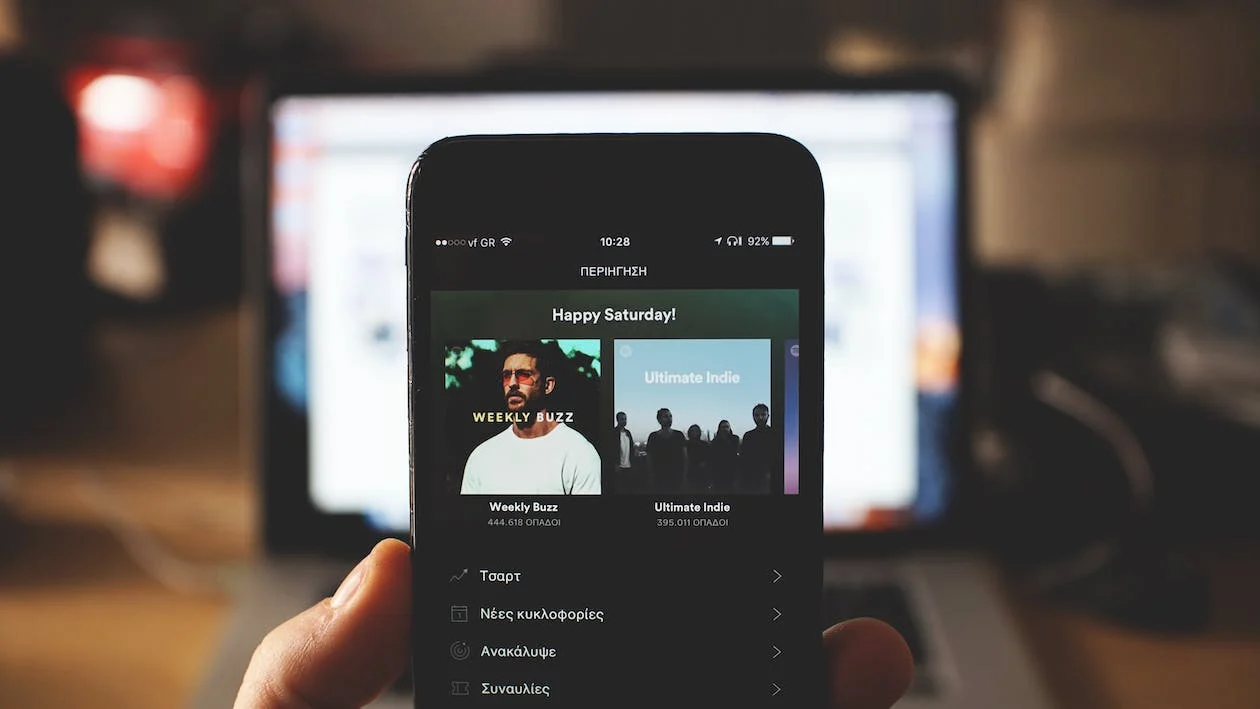

Spotify appears to be taking a different path, upsetting its own main product by incorporating it into a new type of tech product dubbed the "Spotify machine" by investors. Daniel Ek, co-founder, envisions a platform for all things audio, from music to podcasts to audiobooks. More goods would lock in more customers at higher subscription prices, as well as more advertising income and more advanced algorithms and payment systems to tie everything together. The strategy includes some startling ambitions, such as a $100 billion annual sales figure in the next decade, which would place it on par with Citigroup Inc. or WalMart Inc.

But, once again, the stakes are tremendous. The tale of different audio channels merging and increasing profit margins is taking a long time to play out; Jefferies analysts predict Spotify's gross margins to be lower in 2024 than in 2021. The podcasting bubble has also burst, and there's no assurance that Spotify's foray into spoken word will be lucrative this year. Audiobooks appear to be yet another lengthy voyage. The notion that these expenditures will not have an impact on music consumption is also questionable: the potential for shocks when one platform offers both Neil Young and Joe Rogan has become clear.

Something much more significant is currently on the way: artificial intelligence. ChatGPT and similar programs are already being treated in the same manner Metallica attacked Napster, with lawsuits and boycotts. It's just a matter of time until AI-generated music makes its way into music platforms — you can already listen to AI-assisted music on Spotify — and the proliferation of auto-tuned vocals and drum loops in pop music has made people simpler for computers to impersonate.