After examining two prehistoric clay tablets that have been likened to the Rosetta Stone, researchers have now found and deciphered a language that has been lost for thousands of years.

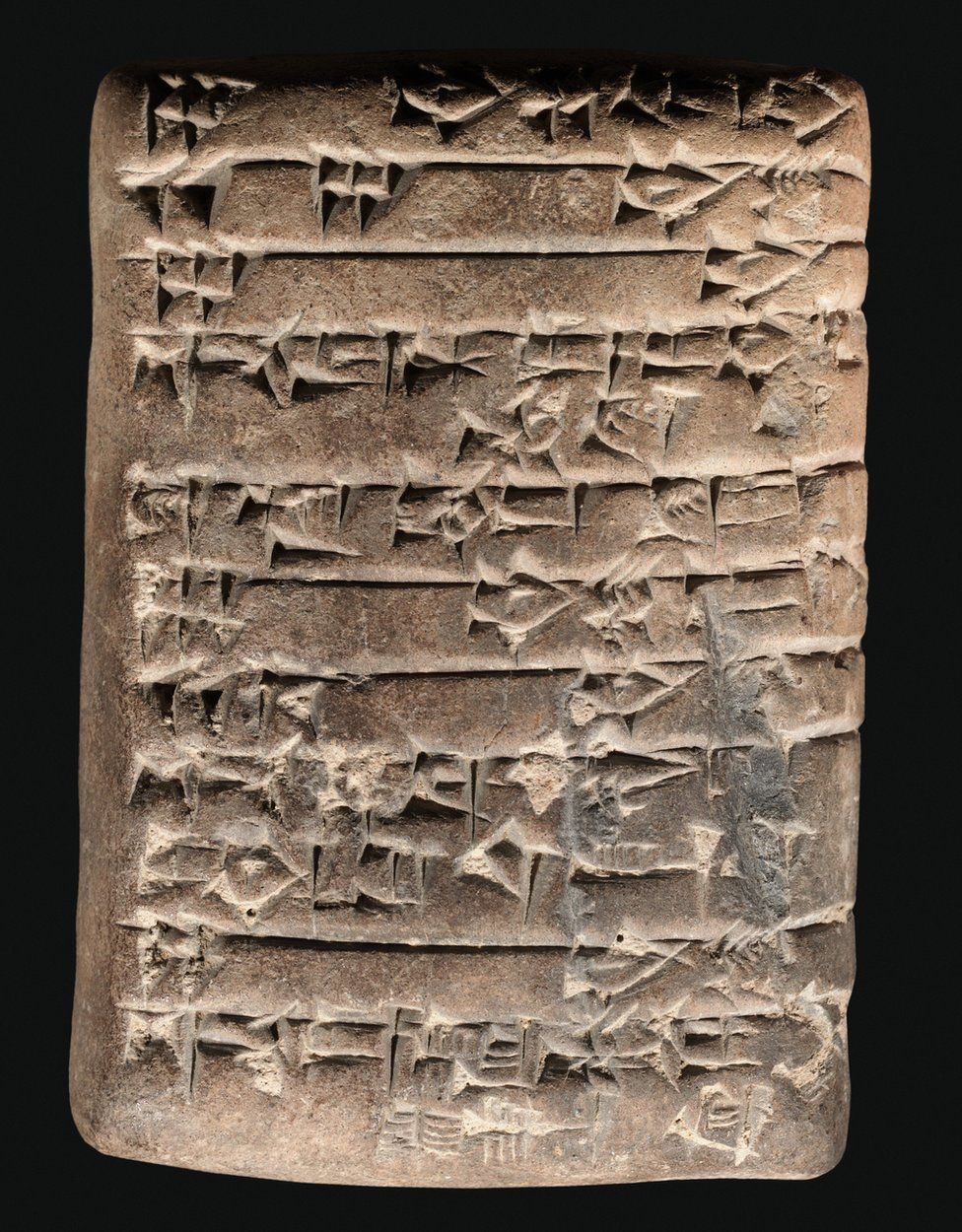

The tablets, which are believed to be 4,000 years old, were found in Iraq many years ago. One was kept in the Jonathan and Jeanette Rosen Cuneiform Collection, while the other was kept in a private collection in London. Manfred Krebernik and Andrew R. George, two academics, have been examining the tablets since 2016. In the French publication Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, also known as the Journal of Assyriology and Eastern Archaeology, the duo published their research in January.

The tablets are written in a landscape format, which is typical of Middle Babylonian Tablets, which originate from the Kassite Period in southern Mesopotamia's first millennium. The tablets seem to have additional traits that are comparable to those of other recently identified features.

According to the authors, the text of both tablets is split into two columns by a vertical ruling, in the fashion of the lists and vocabularies that are characteristic of Babylonian educational learning. The Old Babylonian dialect of the Akkadian language is used in the right-hand columns.

The opposite side, however, was discovered to contain something remarkable: a forgotten language with very few surviving specimens, despite longstanding theories to the contrary. The two tablets' left-hand columns give the astounding material. They include writing that reproduces a North-West Semitic language in many ways. According to the writers, the material on the right side of the tablet is intended to interpret the mysterious language on the left side, so assisting them in decoding it.

Beginning in the early second century, two-column academic lists were customarily formatted as follows: The right-hand column should describe, line by line, the content in the left-hand column.

The researchers were able to infer from the words and phrases that the left hand language was probably the extinct Amorite language and the right hand language was Akkadian's counterpart. Hebrew's ancestor, Amorite, is only known to us from a small number of nouns. It is completely debunked by the material on the tablets.